while

Bank of America topped one U.S. ranking, and

CyberSURF peaked in Canada,

but

Cleveland Clinic cleaned up its act.

while

Bank of America topped one U.S. ranking, and

CyberSURF peaked in Canada,

but

Cleveland Clinic cleaned up its act.

More on those and other interesting rankings in later posts.

-jsq

while

Bank of America topped one U.S. ranking, and

CyberSURF peaked in Canada,

but

Cleveland Clinic cleaned up its act.

while

Bank of America topped one U.S. ranking, and

CyberSURF peaked in Canada,

but

Cleveland Clinic cleaned up its act.

More on those and other interesting rankings in later posts.

-jsq

Here’s why to look at more than one spam data source:

according to the PSBL volume data for November 2011,

Cleveland Clinic’s AS 22093 CCF-NETWORK spewed more than a hundred

spam messages a day on multiple days, while

CBL volume data showed Cleveland Clinic with only 42 spam messages for the entire month.

Apparently PSBL’s spamtraps happened to be in the path of this CCF spam.

Here’s why to look at more than one spam data source:

according to the PSBL volume data for November 2011,

Cleveland Clinic’s AS 22093 CCF-NETWORK spewed more than a hundred

spam messages a day on multiple days, while

CBL volume data showed Cleveland Clinic with only 42 spam messages for the entire month.

Apparently PSBL’s spamtraps happened to be in the path of this CCF spam.

Now a couple of hundred spam messages a day isn’t much by world organization standards, but compared to what we’d all like to see from medical organizations (zero), it’s a lot.

Also compared to the other medical institutions in the same rankings

from the same data,

the pie chart

looks like Pac Man and

the bar graph

looks like a hockey stick.

Also compared to the other medical institutions in the same rankings

from the same data,

the pie chart

looks like Pac Man and

the bar graph

looks like a hockey stick.

Maybe Cleveland Clinic didn’t get the memo after all.

-jsq

At the Telecommunications Policy and Research Conference in Arlington, VA in September, I gave a paper about Rustock Botnet and ASNs. Most of the paper is about effects of a specific takedown (March 2011) and a specific slowdown (December 2010) on specific botnets (Rustock, Lethic, Maazben, etc.) and specific ASNs (Korea Telecom’s AS 4766, India’s National Internet Backbone’s AS 9829, and many others).

The detailed drilldowns also motivate a higher level policy discussion.

There is extensive theoretical literature that indicates Continue readingKnock one down, two more pop up: Whack-a-mole is fun, but not a solution. Need many more takedowns, oor many more organizations playing. How do we get orgs to do that? …

Born out of 2010 meetings organized by the Anti-Phishing Working Group and the IEEE Standards Association, Stop-eCrime has already been working on ecrime event data exchange standards and protocols, as well as operational protocols for dealing with computers compromised by ecrime.

Now Stop-eCrime wants you to help tie these technical and operational levels together into an ecrime detection and response system coordinated among the public, business, academia, and government. There’s plenty of work to be done on technical standards and operational protocols (such as glossaries, metrics, and monetary effects), plus Stop-eCrime needs educational materials and marketing to explain incentives for everyone to participate in reducing ecrime.

Here are the details.

If you want to help, or if you have questions, contact:

https://mentor.ieee.org/stop-ecrime

Chair: Paul Laudanski <paul@laudanski.com>

-jsq

Fahmida Y. Rashid wrote in eWeek.com 8 June 2011, UT Researchers Launch SpamRankings to Flag Hospitals Hijacked by Spammers:

That’s a pretty good explanation for why outbound spam is a proxy for poor infosec.“Poor security measures are generally responsible for employee workstations getting compromised, either by spam or malicious Web content. Once the machine is compromised, the botnet herders can add it to its spam-spewing botnet to send out malware to even more people. The original employee or the organization rarely has any idea the machine has been hijacked for this purpose.”

-jsq

Internet security is in a position similar to that of safety in the medical industry. Many doctors have an opinion like this one,

quoted by

Kent Bottles:

Internet security is in a position similar to that of safety in the medical industry. Many doctors have an opinion like this one,

quoted by

Kent Bottles:

“Only 33% of my patients with diabetes have glycated hemoglobin levels that are at goal. Only 44% have cholesterol levels at goal. A measly 26% have blood pressure at goal. All my grades are well below my institution’s targets.” And she says, “I don’t even bother checking the results anymore. I just quietly push the reports under my pile of unread journals, phone messages, insurance forms, and prior authorizations.”

Meanwhile, according to the CDC, 99,000 people die in the U.S. per year because of health-care associated infections. That is equivalent of an airliner crash every day. It’s three times the rate of deaths by automobile accidents.

The basic medical error problems

observed by Dennis Quaid when his twin babies almost died

due to repeated massive medically-administered overdoses

and due to software problems such as

ably analysed by Nancy Leveson

for the infamous 1980s Therac-25 cancer-radiation device

are not in any way unique to computing in medicine.

The solutions to those problems are analogous to some of the solutions

IT security needs: measurements plus

six or seven layers of aggregation, analysis, and distribution.

The basic medical error problems

observed by Dennis Quaid when his twin babies almost died

due to repeated massive medically-administered overdoses

and due to software problems such as

ably analysed by Nancy Leveson

for the infamous 1980s Therac-25 cancer-radiation device

are not in any way unique to computing in medicine.

The solutions to those problems are analogous to some of the solutions

IT security needs: measurements plus

six or seven layers of aggregation, analysis, and distribution.

As Gardiner Harris reported in the New York Times, August 20, 2010, another problem is that intravenous and feeding tubes are not distinguished by shape or color: Continue reading

I’m giving a talk today at the Internet2 workshop on

Collaborative Data-Driven Security for High Performance Networks

at WUSTL, St. Louis, MO.

You can follow along

with the PDF.

I’m giving a talk today at the Internet2 workshop on

Collaborative Data-Driven Security for High Performance Networks

at WUSTL, St. Louis, MO.

You can follow along

with the PDF.

There may be some twittering on #DDCSW.

-jsq

My point was that 150 years after the invention of epidemiology

and 100 years after the discovery of bacterial transmission of disease,

in medicine application of known preventive measures is so low that

Atul Gawande of Harvard

has gotten large (on the order of 30%) reductions in deaths from complications

of surgery in many hospitals simply by getting them to use checklists for

things like washing hands before surgery.

My point was that 150 years after the invention of epidemiology

and 100 years after the discovery of bacterial transmission of disease,

in medicine application of known preventive measures is so low that

Atul Gawande of Harvard

has gotten large (on the order of 30%) reductions in deaths from complications

of surgery in many hospitals simply by getting them to use checklists for

things like washing hands before surgery.

I have an elderly relative in a nursing home who can’t take pills whole due to some damage to nerves in her neck. Again and again visitors sent by the family discover nursing home staff trying to give her pills whole without grinding them up. Why? They don’t read instructions about her, and previous shifts don’t remind later shifts. This kind of communication problem is epidemic not only in nursing homes but in hospitals. I found my father in a diabetic coma because nurses hadn’t paid any attention to him being a diabetic and needing to eat frequently. Fortunately, a bit of honey brought him out of it. Even nurses readily acknowledge this problem, but it persists. I can rattle off many other examples.

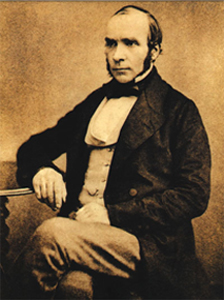

To which someone responded, yes, but medicine has epidemiology,

and Edward Tufte demonstrated in one of his books that that goes

well beyond checklists in to actual analysis, as in a physician’s

discovery of a well in London being he source of cholera.

I responded, yes, John Snow, in 1854:

that was the first thing I said when I stood up to address this.

But who now applies what he learned?

One-shot longitudinal studies are not the same as ongoing monitoring

with comparable metrics to show how well one group is doing compared

to both the known science and to other groups.

To which someone responded, yes, but medicine has epidemiology,

and Edward Tufte demonstrated in one of his books that that goes

well beyond checklists in to actual analysis, as in a physician’s

discovery of a well in London being he source of cholera.

I responded, yes, John Snow, in 1854:

that was the first thing I said when I stood up to address this.

But who now applies what he learned?

One-shot longitudinal studies are not the same as ongoing monitoring

with comparable metrics to show how well one group is doing compared

to both the known science and to other groups.

Many people still didn’t get it, and kept referring to checklists as rudimentary.

So I tried again.

If John Snow were alive today, he wouldn’t be prescribing statins for

life to people with high blood pressure.

He would be compiling data on who has high blood pressure and what

they have been doing and eating before they got it.

He would follow this evidence back to discover that one of the main

contributors to high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes

in the U.S. is

high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Then he would mount a political campaign to ban high fructose corn syrup,

which would be the modern equivalent of his removal of the handle from

the pump of the well that stopped the cholera.

So I tried again.

If John Snow were alive today, he wouldn’t be prescribing statins for

life to people with high blood pressure.

He would be compiling data on who has high blood pressure and what

they have been doing and eating before they got it.

He would follow this evidence back to discover that one of the main

contributors to high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes

in the U.S. is

high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Then he would mount a political campaign to ban high fructose corn syrup,

which would be the modern equivalent of his removal of the handle from

the pump of the well that stopped the cholera.

To which someone replied, but there are political forces who would oppose that. And I said, yes, of course. Permit me to elaborate.

There were political forces in John Snow’s time, too, and he dealt with them:

There were political forces in John Snow’s time, too, and he dealt with them:

Dr Snow took a sample of water from the pump, and, on examining it under a microscope, found that it contained “white, flocculent particles.” By 7 September, he was convinced that these were the source of infection, and he took his findings to the Board of Guardians of St James’s Parish, in whose parish the pump fell.Snow also investigated several outliers, all of which turned out to involve people actually travelling to the Soho well to get water.Though they were reluctant to believe him, they agreed to remove the pump handle as an experiment. When they did so, the spread of cholera dramatically stopped. [actually the outbreak had already lessened for several days]

Still no one believed Snow. A report by the Board of Health a few months later dismissed his “suggestions” that “the real cause of whatever was peculiar in the case lay in the general use of one particular well, situate [sic] at Broad Street in the middle of the district, and having (it was imagined) its waters contaminated by the rice-water evacuations of cholera patients. After careful inquiry,” the report concluded, “we see no reason to adopt this belief.”John Snow didn’t shy away from politics. He was successful in getting the local politicians to agree to his first experiment, which was successful in helping end that outbreak of cholera. He even drew his biggest opponent into doing research, which ended up confirming Snow’s epidemiological diagnosis and extending it further to find the original probable source of infection of the well. But even that didn’t suffice for motivating enough political will to fix the problem.So what had caused the cholera outbreak? The Reverend Henry Whitehead, vicar of St Luke’s church, Berwick Street, believed that it had been caused by divine intervention, and he undertook his own report on the epidemic in order to prove his point. However, his findings merely confirmed what Snow had claimed, a fact that he was honest enough to own up to. Furthermore, Whitehead helped Snow to isolate a single probable cause of the whole infection: just before the Soho epidemic had occurred, a child living at number 40 Broad Street had been taken ill with cholera symptoms, and its nappies had been steeped in water which was subsequently tipped into a leaking cesspool situated only three feet from the Broad Street well.

Whitehead’s findings were published in The Builder a year later, along with a report on living conditions in Soho, undertaken by the magazine itself. They found that no improvements at all had been made during the intervening year. “Even in Broad-street it would appear that little has since been done… In St Anne’s-Place, and St Anne’s-Court, the open cesspools are still to be seen; in the court, so far as we could learn, no change has been made; so that here, in spite of the late numerous deaths, we have all the materials for a fresh epidemic… In some [houses] the water-butts were in deep cellars, close to the undrained cesspool… The overcrowding appears to increase…” The Builder went on to recommend “the immediate abandonment and clearing away of all cesspools — not the disguise of them, but their complete removal.”

Nothing much was done about it. Soho was to remain a dangerous place for some time to come.

From which I draw two conclusions:

As someone at Metricon said, who will watch the watchers? I responded, yes, that’s it!

One-shot longitudinal studies can create great information. That’s what John Snow did. That’s what much of scientific experiment is about. But even when you repeat the experiment to confirm it, that’s not the same as ongoing monitoring. And it’s not the same as checklists to ensure application of what was learned in the experiment.

What is really needed is longitudinal experiments combined

checklists, plus ongoing monitoring, plus new analysis derived

from the monitoring data.

That’s at least four levels.

All of them are needed.

Modern medicine often only manages the first.

And in the case of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS),

until recently even the first was lacking,

and most of the experiments that have happened

until very recently have not come from the country

with the biggest HFCS health problem, namely the U.S.

A third of the entire U.S. population is obese, and another

third is overweight, with concomittant epidemics of

heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

And the medical profession prescribes statins for life

instead of getting to the root of the problem and fixing it.

What is really needed is longitudinal experiments combined

checklists, plus ongoing monitoring, plus new analysis derived

from the monitoring data.

That’s at least four levels.

All of them are needed.

Modern medicine often only manages the first.

And in the case of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS),

until recently even the first was lacking,

and most of the experiments that have happened

until very recently have not come from the country

with the biggest HFCS health problem, namely the U.S.

A third of the entire U.S. population is obese, and another

third is overweight, with concomittant epidemics of

heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

And the medical profession prescribes statins for life

instead of getting to the root of the problem and fixing it.

Yes, I think the field of medicine gets rated too much green for good.

And if IT security wants to improve its own act, it also needs all four levels, not just the first or the second.

-jsq

Good show! What effects did it have on spam? Not just spam from this botnet; spam in general.

This graph was presented at NANOG 48, Austin, TX, 24 Feb 2010, in FireEye’s Ozdok Botnet Takedown In Spam Blocklists and Volume Observed by IIAR Project, CREC, UT Austin. John S. Quarterman, Quarterman Creations, Prof. Andrew Whinston, PI CREC, UT Austin. That was a snapshot of an ongoing project, Incentives, Insurance and Audited Reputation: An Economic Approach to Controlling Spam (IIAR).

That presentation was enough to demonstrate the main point: takedowns are good, but we need a lot more of them and a lot more coordinated if we are to make a real dent in spam.

The IIAR project will keep drilling down in the data and building up models. One goal is to build a reputation system to show how effective takedowns and other anti-spam measures are, on which ASNs.

Thanks especially to CBL and to Team Cymru for very useful data, and to FireEye for a successful takedown.

We’re all ears for further takedowns to examine.

-jsq