Category Archives: Prevention

Quis custodiet ipsos medici?

Internet security is in a position similar to that of safety in the medical industry. Many doctors have an opinion like this one,

quoted by

Kent Bottles:

Internet security is in a position similar to that of safety in the medical industry. Many doctors have an opinion like this one,

quoted by

Kent Bottles:

“Only 33% of my patients with diabetes have glycated hemoglobin levels that are at goal. Only 44% have cholesterol levels at goal. A measly 26% have blood pressure at goal. All my grades are well below my institution’s targets.” And she says, “I don’t even bother checking the results anymore. I just quietly push the reports under my pile of unread journals, phone messages, insurance forms, and prior authorizations.”

Meanwhile, according to the CDC, 99,000 people die in the U.S. per year because of health-care associated infections. That is equivalent of an airliner crash every day. It’s three times the rate of deaths by automobile accidents.

The basic medical error problems

observed by Dennis Quaid when his twin babies almost died

due to repeated massive medically-administered overdoses

and due to software problems such as

ably analysed by Nancy Leveson

for the infamous 1980s Therac-25 cancer-radiation device

are not in any way unique to computing in medicine.

The solutions to those problems are analogous to some of the solutions

IT security needs: measurements plus

six or seven layers of aggregation, analysis, and distribution.

The basic medical error problems

observed by Dennis Quaid when his twin babies almost died

due to repeated massive medically-administered overdoses

and due to software problems such as

ably analysed by Nancy Leveson

for the infamous 1980s Therac-25 cancer-radiation device

are not in any way unique to computing in medicine.

The solutions to those problems are analogous to some of the solutions

IT security needs: measurements plus

six or seven layers of aggregation, analysis, and distribution.

As Gardiner Harris reported in the New York Times, August 20, 2010, another problem is that intravenous and feeding tubes are not distinguished by shape or color: Continue reading

What we can learn from the Therac-25

What does

Nancy Leveson’s

classic

analysis of the

Therac-25 recommend?

(“An Investigation of the Therac-25 Accidents,”

by Nancy Leveson, University of Washington and

Clark S. Turner, University of California, Irvine,

IEEE Computer, Vol. 26, No. 7, July 1993, pp. 18-41.)

What does

Nancy Leveson’s

classic

analysis of the

Therac-25 recommend?

(“An Investigation of the Therac-25 Accidents,”

by Nancy Leveson, University of Washington and

Clark S. Turner, University of California, Irvine,

IEEE Computer, Vol. 26, No. 7, July 1993, pp. 18-41.)

“Inadequate Investigation or Followup on Accident Reports. Every company building safety-critical systems should have audit trails and analysis procedures that are applied whenever any hint of a problem is found that might lead to an accident.” p. 47The lesson being that you have to have built-in audit, reporting, transparency, and user visibility for reputation.“Government Oversight and Standards. Once the FDA got involved in the Therac-25, their response was impressive, especially considering how little experience they had with similar problems in computer-controlled medical devices. Since the Therac-25 events, the FDA has moved to improve the reporting system and to augment their procedures and guidelines to include software. The input and pressure from the user group was also important in getting the machine fixed and provides an important lesson to users in other industries.” pp. 48-49

Which is exactly what Dennis Quaid is asking for.

Remember, most of those 99,000 deaths a year from medical errors aren’t due to control of complicated therapy equipment: Continue reading

Data, Reputation, and Certification Against Spam

I’m giving a talk today at the Internet2 workshop on

Collaborative Data-Driven Security for High Performance Networks

at WUSTL, St. Louis, MO.

You can follow along

with the PDF.

I’m giving a talk today at the Internet2 workshop on

Collaborative Data-Driven Security for High Performance Networks

at WUSTL, St. Louis, MO.

You can follow along

with the PDF.

There may be some twittering on #DDCSW.

-jsq

Medical Metrics Considered Overrated

My point was that 150 years after the invention of epidemiology

and 100 years after the discovery of bacterial transmission of disease,

in medicine application of known preventive measures is so low that

Atul Gawande of Harvard

has gotten large (on the order of 30%) reductions in deaths from complications

of surgery in many hospitals simply by getting them to use checklists for

things like washing hands before surgery.

My point was that 150 years after the invention of epidemiology

and 100 years after the discovery of bacterial transmission of disease,

in medicine application of known preventive measures is so low that

Atul Gawande of Harvard

has gotten large (on the order of 30%) reductions in deaths from complications

of surgery in many hospitals simply by getting them to use checklists for

things like washing hands before surgery.

I have an elderly relative in a nursing home who can’t take pills whole due to some damage to nerves in her neck. Again and again visitors sent by the family discover nursing home staff trying to give her pills whole without grinding them up. Why? They don’t read instructions about her, and previous shifts don’t remind later shifts. This kind of communication problem is epidemic not only in nursing homes but in hospitals. I found my father in a diabetic coma because nurses hadn’t paid any attention to him being a diabetic and needing to eat frequently. Fortunately, a bit of honey brought him out of it. Even nurses readily acknowledge this problem, but it persists. I can rattle off many other examples.

To which someone responded, yes, but medicine has epidemiology,

and Edward Tufte demonstrated in one of his books that that goes

well beyond checklists in to actual analysis, as in a physician’s

discovery of a well in London being he source of cholera.

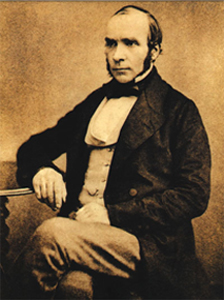

I responded, yes, John Snow, in 1854:

that was the first thing I said when I stood up to address this.

But who now applies what he learned?

One-shot longitudinal studies are not the same as ongoing monitoring

with comparable metrics to show how well one group is doing compared

to both the known science and to other groups.

To which someone responded, yes, but medicine has epidemiology,

and Edward Tufte demonstrated in one of his books that that goes

well beyond checklists in to actual analysis, as in a physician’s

discovery of a well in London being he source of cholera.

I responded, yes, John Snow, in 1854:

that was the first thing I said when I stood up to address this.

But who now applies what he learned?

One-shot longitudinal studies are not the same as ongoing monitoring

with comparable metrics to show how well one group is doing compared

to both the known science and to other groups.

Many people still didn’t get it, and kept referring to checklists as rudimentary.

So I tried again.

If John Snow were alive today, he wouldn’t be prescribing statins for

life to people with high blood pressure.

He would be compiling data on who has high blood pressure and what

they have been doing and eating before they got it.

He would follow this evidence back to discover that one of the main

contributors to high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes

in the U.S. is

high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Then he would mount a political campaign to ban high fructose corn syrup,

which would be the modern equivalent of his removal of the handle from

the pump of the well that stopped the cholera.

So I tried again.

If John Snow were alive today, he wouldn’t be prescribing statins for

life to people with high blood pressure.

He would be compiling data on who has high blood pressure and what

they have been doing and eating before they got it.

He would follow this evidence back to discover that one of the main

contributors to high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes

in the U.S. is

high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Then he would mount a political campaign to ban high fructose corn syrup,

which would be the modern equivalent of his removal of the handle from

the pump of the well that stopped the cholera.

To which someone replied, but there are political forces who would oppose that. And I said, yes, of course. Permit me to elaborate.

There were political forces in John Snow’s time, too, and he dealt with them:

There were political forces in John Snow’s time, too, and he dealt with them:

Dr Snow took a sample of water from the pump, and, on examining it under a microscope, found that it contained “white, flocculent particles.” By 7 September, he was convinced that these were the source of infection, and he took his findings to the Board of Guardians of St James’s Parish, in whose parish the pump fell.Snow also investigated several outliers, all of which turned out to involve people actually travelling to the Soho well to get water.Though they were reluctant to believe him, they agreed to remove the pump handle as an experiment. When they did so, the spread of cholera dramatically stopped. [actually the outbreak had already lessened for several days]

Still no one believed Snow. A report by the Board of Health a few months later dismissed his “suggestions” that “the real cause of whatever was peculiar in the case lay in the general use of one particular well, situate [sic] at Broad Street in the middle of the district, and having (it was imagined) its waters contaminated by the rice-water evacuations of cholera patients. After careful inquiry,” the report concluded, “we see no reason to adopt this belief.”John Snow didn’t shy away from politics. He was successful in getting the local politicians to agree to his first experiment, which was successful in helping end that outbreak of cholera. He even drew his biggest opponent into doing research, which ended up confirming Snow’s epidemiological diagnosis and extending it further to find the original probable source of infection of the well. But even that didn’t suffice for motivating enough political will to fix the problem.So what had caused the cholera outbreak? The Reverend Henry Whitehead, vicar of St Luke’s church, Berwick Street, believed that it had been caused by divine intervention, and he undertook his own report on the epidemic in order to prove his point. However, his findings merely confirmed what Snow had claimed, a fact that he was honest enough to own up to. Furthermore, Whitehead helped Snow to isolate a single probable cause of the whole infection: just before the Soho epidemic had occurred, a child living at number 40 Broad Street had been taken ill with cholera symptoms, and its nappies had been steeped in water which was subsequently tipped into a leaking cesspool situated only three feet from the Broad Street well.

Whitehead’s findings were published in The Builder a year later, along with a report on living conditions in Soho, undertaken by the magazine itself. They found that no improvements at all had been made during the intervening year. “Even in Broad-street it would appear that little has since been done… In St Anne’s-Place, and St Anne’s-Court, the open cesspools are still to be seen; in the court, so far as we could learn, no change has been made; so that here, in spite of the late numerous deaths, we have all the materials for a fresh epidemic… In some [houses] the water-butts were in deep cellars, close to the undrained cesspool… The overcrowding appears to increase…” The Builder went on to recommend “the immediate abandonment and clearing away of all cesspools — not the disguise of them, but their complete removal.”

Nothing much was done about it. Soho was to remain a dangerous place for some time to come.

From which I draw two conclusions:

-

Even John Snow is over-rated.

Sure, he found the problem, but he didn’t get it fixed longterm.

- Why not? Because that would require ongoing monitoring of likely sources of infection (which sort of happened) compared to actual incidents of disease (which does not appear to have happened), together with eliminating the known likely sources.

As someone at Metricon said, who will watch the watchers? I responded, yes, that’s it!

One-shot longitudinal studies can create great information. That’s what John Snow did. That’s what much of scientific experiment is about. But even when you repeat the experiment to confirm it, that’s not the same as ongoing monitoring. And it’s not the same as checklists to ensure application of what was learned in the experiment.

What is really needed is longitudinal experiments combined

checklists, plus ongoing monitoring, plus new analysis derived

from the monitoring data.

That’s at least four levels.

All of them are needed.

Modern medicine often only manages the first.

And in the case of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS),

until recently even the first was lacking,

and most of the experiments that have happened

until very recently have not come from the country

with the biggest HFCS health problem, namely the U.S.

A third of the entire U.S. population is obese, and another

third is overweight, with concomittant epidemics of

heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

And the medical profession prescribes statins for life

instead of getting to the root of the problem and fixing it.

What is really needed is longitudinal experiments combined

checklists, plus ongoing monitoring, plus new analysis derived

from the monitoring data.

That’s at least four levels.

All of them are needed.

Modern medicine often only manages the first.

And in the case of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS),

until recently even the first was lacking,

and most of the experiments that have happened

until very recently have not come from the country

with the biggest HFCS health problem, namely the U.S.

A third of the entire U.S. population is obese, and another

third is overweight, with concomittant epidemics of

heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

And the medical profession prescribes statins for life

instead of getting to the root of the problem and fixing it.

Yes, I think the field of medicine gets rated too much green for good.

And if IT security wants to improve its own act, it also needs all four levels, not just the first or the second.

-jsq

Community Flow-spec Project

Update: PDF of presentation slides here.

+--------+--------------------+--------------------------+ | type | extended community | encoding | +--------+--------------------+--------------------------+ | 0x8006 | traffic-rate | 2-byte as#, 4-byte float | | 0x8007 | traffic-action | bitmask | | 0x8008 | redirect | 6-byte Route Target | | 0x8009 | traffic-marking | DSCP value | +--------+--------------------+--------------------------+

A few selected points:

- Dissemination of Flow Specification Rules

- Think of filters(ACLs) distributed via BGP

- BGP possibly not the right mechanism

- Multi-hop real-time black hole on steroids

-

Abuse Handler + Peering Coordinator

= Abeering Coordinator? - Traditional bogon feed as source prefix flow routes

- A la carte feeds (troublesome IP multicast groups, etc.)

- AS path prepend++

- Feed-specific community + no-export

Trust issues for routes defined by victim networks.

Research prototype is set up. For questions, comments, setup, contact: http://www.cymru.com/jtk/

I like it as an example of collective action against the bad guys. How to deal with the trust issues seems the biggest item to me.

Hm, at least to the participating community, this is a reputation system.

Checks on Checks, or Shipping and Shipping Software

Paul Graham points out that big company checks on purchasing

usually have costs, such as purchasing checks increase the costs of

purchased items because the vendors have to factor in their costs

of passing the checks.

Paul Graham points out that big company checks on purchasing

usually have costs, such as purchasing checks increase the costs of

purchased items because the vendors have to factor in their costs

of passing the checks.

Such things happen constantly to the biggest organizations of all, governments. But checks instituted by governments can cause much worse problems than merely overpaying. Checks instituted by governments can cripple a country’s whole economy. Up till about 1400, China was richer and more technologically advanced than Europe. One reason Europe pulled ahead was that the Chinese government restricted long trading voyages. So it was left to the Europeans to explore and eventually to dominate the rest of the world, including China.I would say western governments (especially the U.S.) subsidizing petroleum production and not renewable energy is one of the biggest source of current world economic, political, and military problems. Of course, lack of checks can also have adverse effects as we’ve just seen with the fancy derivatives the shadow banking system sold in a pyramid scheme throughout the world. It’s like there should be a balance on checks. Which I suppose is Graham’s point: without taking into account the costs of checks (and I would argue also the risks of not having checks), how can you strike such a balance?— The Other Half of “Artists Ship”, by Paul Graham, November 2008

He doesn’t neglect to apply his hypothesis to SOX: Continue reading

Confusopoly, or Scott Adams, Prophet of Finance

While sitting in a small room perusing a book from the bottom of the stack, The Dilbert Future, I idly looked again at Scott Adam’s prediction #2:

While sitting in a small room perusing a book from the bottom of the stack, The Dilbert Future, I idly looked again at Scott Adam’s prediction #2:

In the future, all barriers to entry will go away and companies will be forced to form what I call “confusopolies”.OK, good snark. But look at the list of industries he identified as already being confusopolies:Confusopoly: A group of companies with similar products who intentionally confuse customers instead of competing on price.

- Telephone service.

- Insurance.

- Mortgage loans.

- Banking.

- Financial servvces.

And the other four are the source of the currrent economic meltdown, precisely because they sold products that customers couldn’t understand. Worse, they didn’t even understand them!

It gets better. What industry does he predict will become a confusopoly next? Electricity! And this was in 1998, before Enron engineered confusing California into an electricity-price budget crisis.

For risk management, perhaps it’s worth considering that simply selling something the customer can understand can rank way up there. Certainly for the customer’s risk. And given how much the FIRE companies drank their own Kool-Aid, apparently it’s good risk management for the company itself. Especially given that the Internet now gives the customer more capability to find out what’s going on behind a confusopoly and more ability to vote with their feet.

To actually make a product the customer wants, and then provide good customer service: how old-fashioned! And how less risky and more profitable in the long term.

Crossing the Street in Cyberspace: Michael Kaiser and the National Cyber Security Alliance

If you grew up in a small town, you’d likely cross the street without stopping to look each way. Try that in New York City, and you’ll end up in the hospital. Similarly, most of us grew up in meatspace and clicking on any old link in cyberspace often ends up with our bank account in the hospital.

If you grew up in a small town, you’d likely cross the street without stopping to look each way. Try that in New York City, and you’ll end up in the hospital. Similarly, most of us grew up in meatspace and clicking on any old link in cyberspace often ends up with our bank account in the hospital.

OK, that was my mangled simile, but it illustrates what Michael Kaiser and the National Security Alliance are trying to do: educate the public about what to do and not do in cyberspace without losing their audience with technical details or lengthy pedantic instructions. In his talk at APWG he had all sorts of interesting points, such as address different audiences (K-12, small business, elderly, etc.) differently, and that it’s not just unlearning bad habits (including ones that would be good habits in other contexts), it’s teaching good habits. ANd changing habits of any kind requires repetition and persistence. As Kaiser said, look at the CDC and its ongoing campaigns of prevention of HIV, domestic violence, etc.

Personally, I think staysafeonline.org could use more graphics and less text, or, more importantly, more storyline. It seems a tad pedantic to me. More poets in prevention! Or more marketing in staying safe. Or something.

But it’s a useful site already.

Teachable Moment: APWG/CMU Phishing Education Landing Page program

Phishing? Fail!

Phishing? Fail!

When you take down a phishing domain or server, don’t just take it off the net: redirect it to this education page so victims of phishing can learn in the act of being suckered by a phisher that they should be more careful what they click on.

As someone in the audience pointed out, whatever you do don’t redirect phishing pages back to the actual sites being phished, i.e., if the phisher was pretending to be a bank, don’t take down the phisher’s redirect and replace it with a redirect to the bank itself. THat just teaches people the wrong thing, to follow a bad link.

Instead, link to the APWG/CMU landing page. Which could use a catchier name (how about Phishing: Fail!), but it’s already a really good service.