Dave Weinberger types out of a drug- and fatigue-induced haze:

Truth is a property of networks.

I can only guess at what I mean, starting with the obvious: Rather than thinking that truth is a relationship between the propositions we believe and the way the world is, such that the propositions represent the world, in the networked world the truth is argued for and connected via links. For all but the most mundane of truths, the network of conversations gives us more shades, nuances, and reasons to believe. Which leads me to think that if truth isn’t an emergent property of networks, then understanding is.

—Networked truth, Dave Weinberger, Joho the Blog, 13 April 2007

I think he’s right, except it’s not either/or: it’s both.

There are truths that aren’t produced by communications: if you jump off a cliff, you fall down. Yet so many people have seen Wile E. Coyote try that and spin his wheels in the air before he looks down that they probably believe they’d do that, too. Probably not many people try it to see, but lots of people believe they can outrun a train, outsmart the market, win the lottery, etc., and try anyway, so their beliefs affect what happens. And their beliefs are strongly affected by their experiences of connections with other people. Seeing lots of other people buying lottery tickets makes buying lottery tickets a self-reinforcing socially acceptable activity.

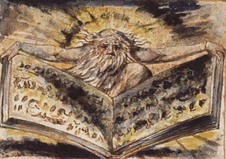

And if there are revealed truths from a higher authority, nonetheless we have to learn to read the words and interpret them according to how our society understands them.

Every occasion involving a sentient being has at least four aspects:

- physical, biological, etc. laws and effects of the material world,

- social interactions (communications) and institutions (governments, social groups, religions, etc.),

- cultural norms that groups derive over time from the above,

- and internal beliefs that come from all the above including our own personal experiences, genetic inheritance, etc.

(If you’re not sentient and are, for example, a chair, skip the cultural and internal belief parts; and yes, these four quadrants are owed to Ken Wilber.)

Dave continues:

It is, of course, an unowned, self-contradictory, unsettled truth that is too big to be contained by any individual. It is outside of us and among us. It is gained not by trying to contain it but by traveling through it.

Boy howdy. And by travelling through it we change. And as we change our interpretations of our networks and our communications change, as we choose different groups, absorb different cultural norms, and learn to deal with the physical world differently. We may even learn a different level of understanding (from following rules to deriving rules; from rules to compassion; etc.).

Speaking of cultural norms, when I wrote "drug- and fatigue-induced haze" I bet that many readers would interpret that as Dave had been on a binge. Actually, he wrote that he had taken Dramamine, which is for motion sickness. Yet in our War on Drugs culture, the first interpretation is far more likely. Unless you followed the link and read the rest of what Dave wrote before forming an opinion, which is in itself a different and perhaps higher form of understanding that most people don’t bother to do.

What has all this got to do with risk management?

Well, validation, to take an example from a recent post, is not just syntax, and not just semantics. It also has to do with interpretation of content in terms of culture and beliefs, in which different people are going to have different interpretations of one and the same text. If your specific problem is preventing input text from being evaluated by a computer as a snippet of a known computer language, you’ve got a chance of preventing that with lists of strings to deny and allow. Even then a sophisticated cracker may think of combinations of characters that you didn’t, or may think of a different language that you didn’t consider.

If instead your problem is

you’ve got a much tougher row to hoe. Well, if you insist on such indications being reasonably accurate. If you’re willing to round up all the usual suspects and eject them or "persuade" them to say what you want them to say, no problem. But that’s not good risk management for your country. And probably not even for you, even if you’re running it, as John Adams found out to his dismay when he lost the presidency to Thomas Jefferson partly over the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Nor good risk management for companies, as HP and its (now ex-) chairman Dunn discovered.

-jsq